Issues & Trends

WLC Panel Explores Implications of Wilkinson v. Garland in Removal Cases

April 12, 2024

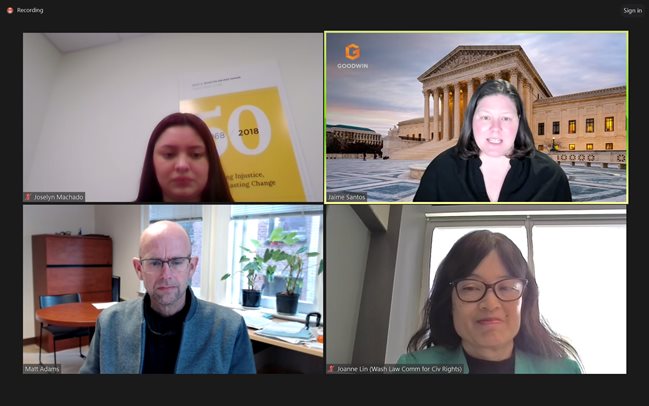

Fresh off her recent victory in the U.S. Supreme Court, Goodwin Procter LLP partner Jaime Santos talked about the impact of Wilkinson v. Garland on cancellation of removal applications at a March 27 panel hosted by the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs (WLC).

In that case, the justices held that federal courts have the ability to review the denial of an immigrant’s application for cancellation of removal based on the hardship that deportation would cause the applicant’s U.S.-born child. It was Santos’s first oral argument before the nation’s highest court.

“Cancellation is one of the many forms of discretionary immigration relief that is available to noncitizens the government is trying to deport,” said Santos, cochair of Goodwin’s appellate and Supreme Court litigation practice and a WLC board member. “It applies if a noncitizen can meet four eligibility requirements. They have to have been in the United States for 10 years. They have to have good moral character. They have to have no disqualifying criminal convictions, and they have to show that their removal would cause ‘exceptional and extremely unusual hardship’ to a U.S. family member.”

Santos’s client, Situ Kamu Wilkinson, a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago, arrived in the United States 21 years ago, fleeing persecution by the police. He has since married a U.S. citizen and had a child, also a U.S. citizen by birth. Wilkinson worked as a handyman and was the sole financial support for his family.

“He is known in his community as the guy who helps senior citizens take their groceries into their homes and fixes things that are broken,” Santos said.

In 2019 police found drugs in a house where Wilkinson was making repairs. He was arrested and detained by federal immigration officers. When the U.S. government commenced removal proceedings against him in 2020 for overstaying his tourist visa (the criminal charges were withdrawn), Wilkinson sought relief in the form of asylum and cancellation of removal.

While Wilkinson met the first three statutory criteria for eligibility, the government disagreed that his deportation would cause exceptional and extremely unusual hardship for his son who has serious medical issues. The immigration judge found that Wilkinson’s hardship did not meet the requisite level of severity to qualify for relief, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled that it had no jurisdiction to review the judge’s determination because it was discretionary.

Santos disagreed, saying that while the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) strips federal courts of the ability to review discretionary forms of relief, they can review constitutional claims and questions of law.

“About four years ago, the [Supreme] Court held in … Guerrero-Lasprilla v. Barr that ‘questions of law’ that courts have jurisdiction to review include the application of a legal standard to settled or established facts,” Santos said.

She argued that the determination in Wilkinson’s case involved just such a mixed question of fact and law and was therefore reviewable by a federal court. The government, on the other hand, argued that the question was primarily, if not entirely, factual and that it involved a discretionary decision by an immigration judge that could not be reviewed.

“The Court issued a 6–3 decision holding that it meant what it said in Guerrero-Lasprilla — that all mixed questions, whether judge-made or statutory, whether fact-bound or not, were questions of law under the INA and that they are reviewable by federal courts,” Santos said.

After being detained for almost four years in the course of litigation, Wilkinson was released in February and has since reunited with his wife and child.

Matt Adams, legal director at the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, described the importance of the Wilkinson decision, saying, “[It was] an amazing result for Mr. Wilkinson, but also for the immigrant community at large, given the impact this will have … in making clear that individuals who are denied cancellation of removal based upon a hardship finding have access to judicial review.”

“To many, that might seem a little abstract, but for those practitioners who are representing people in deportation proceedings, we are well aware of the fact that cancellation of removal for nonpermanent residents is one of the primary forms of relief for people who don’t have legal status in this country,” Adams added.

Adams said that the broad discretionary powers held by immigration courts have made representation a frustrating and sometimes futile effort. He pointed out that the courts’ discretionary powers largely originate under the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, and since then there have been few court decisions that discuss the standard of unusual hardship.

“Unfortunately, the way that plays out is that immigration judges have so much room to decide whether they are going to grant discretionary relief based on this hardship finding, so you have people who are regularly denied that are facing unconscionable hardship,” he said. “Now, with this decision, advocates are going to be able to file petitions for review, and we’re going to be able to start to flesh out the case law here that lays out more concrete guidelines for what constitutes exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.”

Wilkinson will have an impact on other issues as well, Adams said. “It necessarily follows, from this court’s decision, that with respect to cancellation of removal for victims of violence under the Violence Against Women Act, which also has a hardship element, that the court retains jurisdiction to, again, apply undisputed facts to see whether they meet this hardship.”

According to Adams, the implications of Wilkinson may yet extend to other discretionary decisions by immigration courts, where undisputed facts are applied to a legal standard.