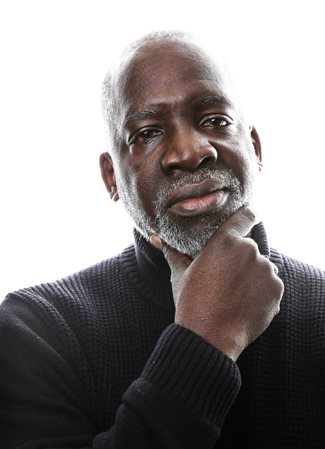

Ask an Expert

Inside Battles of Band Trademarks With IP Attorney Fred Samuels

October 18, 2023

In January 2023, intellectual property attorney Fred Samuels began representing Verne Allison and Michael “Mickey” McGill, the last two surviving members of the iconic R&B singing group the Dells, whose string of timeless hits included “Oh, What a Night,” “Stay in My Corner,” and “I Can Sing a Rainbow.”

“Mickey” McGill, the last two surviving members of the iconic R&B singing group the Dells, whose string of timeless hits included “Oh, What a Night,” “Stay in My Corner,” and “I Can Sing a Rainbow.”

For years Allison and McGill had tried to stop a group billing itself as the Dells Revue from singing and dressing in the Dells’ likeness while performing the group’s hits on tour — without enlisting or consulting the original members.

Those efforts, however, were in vain. “So, the Dells hired me,” says Samuels, partner at Cahn & Samuels, LLP.

The legal battle between the Dells and the Dells Revue is far from unique in the music industry. Here, Samuels talks about the legal issues that may come up for tribute bands and former bandmates of legacy groups who use the name of their former acts, the trademarking process with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and his recommendations for musicians and other artists faced with trademark disputes.

What do musicians and artists need to do to trademark their name?

The way trademarks work [in this case] is that [a band performing] under a particular name develops trademark rights merely from the fact that they have been performing under that name and they have come to be known under that name. So, that is the bare minimum that they need to do.

It is advisable for a band to register their trademark with the USPTO. That gives them additional rights … and then they can pursue an infringer based on their federal registration. But once you can establish that you have been performing, have adopted a name, and people have come to know you by that name, that is really all you need to pursue someone who comes along and trades off that name.

Do you see more artists trademarking their names now compared to previous decades?

If you look back a little bit further, I think it was far rarer for bands to be advised to register their trademarks. In some instances, a record company would take ownership of the band’s name, and the band [wouldn’t] even know to negotiate that in their recording contract. I would say since the ’90s, the advice that bands get has been more fulsome.

Walk us through the process of trademarking a band or stage name and how much it costs.

Registering a trademark is something that will probably cost you between $1,000 and $2,000, depending on what happens in the process, and that includes attorney’s fees, which can vary depending on who you use. There are some government fees that you have to pay as well. The Patent and Trademark Office charges a fee ($250) for each category that you want to register your mark in. Bands often file in two categories, which would be live musical performance and sound recordings, because if they are recording, they want their name protected with respect to their sound recordings as well.

Then you file an application. Right now, USPTO is running about eight or nine months before they respond to your application, and they will compare it to other applications to see whether there is a confusingly similar mark out there or whether your application meets some of the other requirements for getting a registration. They will send out a report, which will either say that you have met everything and you are now going to the next phase, or that you are too close to another trademark or have not met some other requirement that there is for registration. Any applicant has the opportunity to do a little back-and-forth with the patent office to try to convince them that they should get a registration.

If they get to the point where the patent office agrees, they will publish the application. They do not grant it to you immediately. They will say, “You have been approved, but we are going to publish it for 30 days,” and in that 30-day period, any member of the public can come in and object to the applicant getting the trademark.

So, for example, let’s say that somebody wanted to register the band name Earth, Wind & Fire, and let’s assume that Earth, Wind & Fire had not been previously registered. They were out there performing, but they just did not register. The patent office is not going to look at what is going on in the public; they are just going to look at what is on the trademark register, so they are going to approve that application. But during this 30-day publication period, Earth, Wind & Fire can come in and object, saying, “Hey, [this person] should not be granted this registration because we have been out here doing this forever.”

That would be a way for the real band to stop the other from getting the registration, and that is what that 30-day publication period is for. It is typically trademark holders who have not registered their mark, but who have developed trademark rights.

In terms of that window, how does the established band get recognized as the original ensemble?

There is a whole process when someone wants to challenge during the opposition period. They have to file a proceeding with the trademark office. It is not just a letter that says, “Hey, I was earlier.” They have to file what is called an opposition proceeding. An opposition proceeding is a little bit like litigation. They file a paper called a petition, and in that petition, they have to make certain allegations about when they started using [the name], how they developed the rights, how long they have had [the name], and that they have had it continuously.

The trademark applicant then gets to respond to that petition, and then there is a period, much like in regular litigation, where you go into discovery and where each side gets to ask the other side for their proof. They get to interrogate witnesses under oath, and they gather all this evidence for a period of time. After the evidence-gathering period, they make a presentation to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board.

All this happens within the trademark office. It is not in a court, but there is a three-judge panel within the trademark office that looks at this evidence and makes a decision … to allow the applicant to register or not. The losing party can appeal that decision.

But it is a bit of an expensive procedure. If an opposition proceeding does not settle and goes through its full life cycle, it can cost anywhere from $40,000 to $50,000 on the lower end to a couple hundred thousand dollars on the higher end, depending upon how intense the evidence is, and so on.

What advice would you give to both ensembles and individuals within a band about trademark ownership when members come and go? I think about some of the woes of various go-go bands in the Washington, D.C., area where different versions of, say, Experience Unlimited are playing in all eight wards at once.

That is not an uncommon occurrence. And there are a couple of ways to look at this. The true owner of a trademark is supposed to be the person or entities that control the nature and quality of the service, and this can get very tricky when it comes to a band, depending upon the dynamics in a band. Maybe everybody is a contributor and it is a collective thing, or maybe the bandleader has the vision and decides the look, the sound, and the lineup.

In the first case, the collective would own the trademark. In the second case, the bandleader would own it, even though there are other members of the band, because [the other members] are not really controlling the nature of the quality of the sound and the identity of the band. [This is] one of the more difficult things [for a court] to unpack … because all artists believe that their contribution is significant. And [the courts] typically err on the side of it being a group of people where the whole group owns it. I have seen that more frequently than a court willing to dig in and look at what is actually happening in a given situation.

So, understanding that, the best advice would really be for a band to come to an agreement early on about what is going to happen with name ownership. That is a bit Pollyannaish, in my experience, because that rarely happens, but that would be the best advice. My experience is typically there is either no discussion or no agreement as to what happens when a person leaves, [when] an original member leaves, or what have you, so it ends up that the departing person is just operating on their own notions of what is fair, which frequently does not comport with what the law says.

What do promoters need to know when dealing with bands that either do not involve the original members of the group or that involve members who do not control the original act’s trademark?

That is a good question because, first of all, promoters should pay attention to trademarks and rights in name and likeness, and they should understand that it is not illegal to have a tribute band per se, but there are certain rules of the road, and they need to pay attention to those. One of the rules of the road is if a tribute band is coming to your venue, you should not use the original artist’s likeness to promote said tribute band. You should use the tribute band’s likeness.

The other thing that promoters should do is [ask] the band if there have been any issues because sometimes there have been and the promoters are unaware, so they can get caught in the crossfire.

In this day and age, most artists have social media, so they are advertising too, but there is something called the Truth in Music Advertising Act, which many states have adopted … and it metes out penalties separate from trademark for advertising bands that use a trademark that is confusingly similar to a known trademark. And if there are no original members in that group that will be performing, that liability is directed to anyone who advertises. So, most frequently, it is going to be the promoter. In some states, that law has both a civil and a criminal element. It is really geared toward promoters who are trying to fool the general public, but it is broad enough that they need to pay attention to that. In the Dells case, we had a Truth in Music claim in the case because it fit that set of criteria.